We Compared 6 Outage Reports Before We Understood What Async Rust Actually Prevents

Table of Contents

- CPU at 58%, Memory Stable, Users Furious

- Nine Months, Six Outages, Same Script

- Node.js, Go, Java: Six Ways Async Systems Die

- The Moment the Latency Graphs Lined Up

- Rewriting One Service with Tokio

- The Rust Compiler Says “No” Before Production Does

- Load Test: Tokio vs Node.js vs Go

- How Many Outages Could Rust’s Async Model Prevent?

- Code Reviews Started Sounding Different

- The Trade-offs Are Real

- The Quietest Change

- Final Thoughts

- FAQ

CPU at 58%, Memory Stable, Users Furious

There’s a particular kind of async service outage that drives people crazy: every metric on the dashboard is green, but users are losing their minds.

CPU hovering at 58%. Memory curve flat as a heart monitor. No deploys in three hours. Yet error rates quietly crept up to 3.4%, all timeouts.

Dashboard looked peaceful. The incident channel was on fire.

It’s like going to the doctor for a checkup — every number comes back normal, but you feel terrible. The doctor looks at the chart and says “everything’s fine,” and you look at the doctor and say “I really don’t feel fine.”

This wasn’t the first time.

Nine Months, Six Outages, Same Script

Zoom out on the timeline: six outages across three different services over nine months. Different teams, different codebases, but the storyline was eerily similar.

The first outage got blamed on a bad downstream. The second was “traffic spike.” The third became “unexpected event loop contention.” By the fourth, the language had shifted: “We are investigating potential async scheduling delays.”

The monitoring graphs looked identical every time:

- CPU within bounds

- No memory leaks

- Request rate as forecasted

- p99 latency through the roof

- Thread pools maxed out

The system looked healthy. Users disagreed.

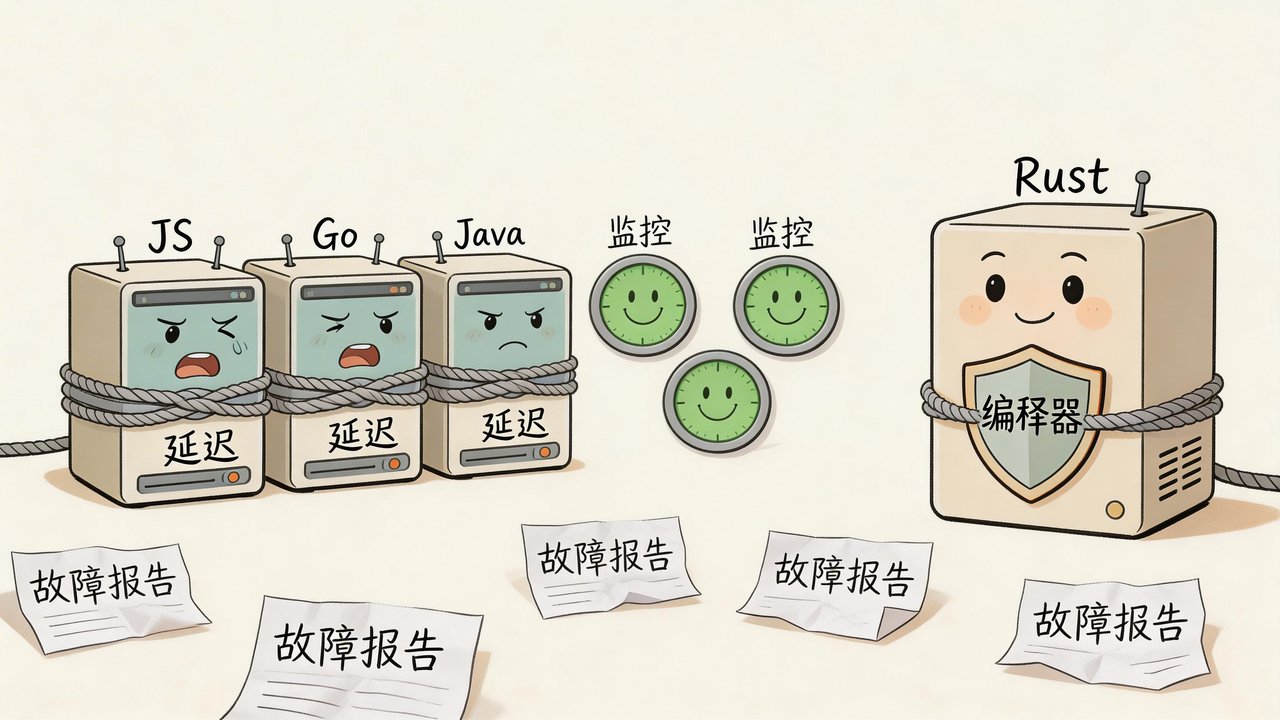

These six services were written in Node.js, Go, and Java (Project Reactor). Different languages, different async runtimes, same way of dying.

Node.js, Go, Java: Six Ways Async Systems Die

Lay out the six outage reports side by side and the root causes differ in detail but rhyme in rhythm:

| Incident | Symptom | Root Cause | Hidden Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | p99 spike | Promise chain depth | Microtask queue starvation |

| #2 | Timeouts | Blocking call in async handler | Event loop stall |

| #3 | Slow degradation | Backpressure misconfiguration | Unbounded queue growth |

| #4 | CPU plateau | Excessive goroutine churn | Scheduler contention |

| #5 | Partial brownout | Retry storm | Async fan-out amplification |

| #6 | Cascading timeouts | Mixed sync/async IO | Thread pool exhaustion |

All six had the same root: coordination cost under load.

None were syntax errors. None were catchable in code review. Every piece of code “looked correct.”

When a traditional threaded service fails, it’s like a burst pipe — loud, messy, easy to find. When an async system fails, it’s more like a slow leak behind drywall. The surface looks fine. By the time you notice, the damage has spread.

The Moment the Latency Graphs Lined Up

The turning point came after the sixth outage.

Someone asked a simple question: “Why do we keep having outages where nothing is technically wrong?”

Then they did something: overlaid the latency graphs from all six incidents.

Nearly identical.

No cliff. No crash. A smooth upward curve, latency stacking on latency, climbing like a staircase.

That curve shape has a name: scheduler pressure.

Async systems degrade differently from threaded ones. They rarely crash. They suffocate.

Think of a traffic jam. The cars aren’t broken. The traffic lights work fine. But every car waits two extra seconds, multiply that by a few thousand cars, and the entire highway grinds to a halt. No single point “failed,” but the system stopped.

That’s what an async scheduler looks like under pressure.

Rewriting One Service with Tokio

They didn’t migrate everything to Rust.

They built one new service using Tokio (1.x stable). Not because Rust was trendy — because they wanted to see what happens when a language turns these things into hard constraints:

- Blocking must be explicitly declared

- Ownership forces you to think about data lifetimes

- Backpressure is designed in, not bolted on

- Async boundaries are visible in the type system

It was slower to write. Nobody disputes that.

But the first interesting artifact wasn’t the performance numbers. It was the shape of the code.

The Rust Compiler Says “No” Before Production Does

Look at this Rust code:

async fn handler(db: &DbPool) -> Result<Response> {

let conn = db.get_conn(); // potentially blocking

let user = fetch_user(conn).await?;

Ok(Response::from(user))

}

In Node.js or Go, this code runs. Runs fine, actually. Until traffic doubles.

In Rust, the compiler forces you to answer a few questions:

- Is

get_conn()blocking? Should it be wrapped inspawn_blocking? - Is this Future

Send? Can it be safely scheduled across threads? - Are you holding a lock across that

.await?

In previous languages, these questions surfaced at runtime — usually at 2 AM, discovered by whoever was on call. In Rust, they’re compile errors. Clippy even has a dedicated await_holding_lock lint for catching locks held across await points, and Tokio’s docs repeatedly emphasize using spawn_blocking to isolate blocking work.

That friction is annoying. It’s also diagnostic.

Like when you try to shove something into your backpack and the zipper jams. You mutter “come on,” yank it open, and find a charging cable tangled around your keys. The zipper wasn’t broken. It was telling you something was wrong inside.

Load Test: Tokio vs Node.js vs Go

Three months later, traffic doubled. Everyone watched the dashboards, waiting for trouble.

Nothing happened.

Still not convinced, they ran a load test. Same hardware, same synthetic workload:

| Metric | Node.js Async Service | Go Service | Rust + Tokio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stable RPS | 21k | 24k | 31k |

| p99 at 2x load | 1.2s | 870ms | 140ms |

| CPU at saturation | 94% | 88% | 76% |

| Memory variance | ±18% | ±12% | ±4% |

The most interesting number in that table isn’t who had the highest RPS. It’s the degradation curve.

Node.js latency under pressure shot up like an elevator. Go was better — more like climbing stairs. Rust was a gentle slope. It’d reach the top eventually, but much later.

Put it in driving terms: three cars stuck in the same traffic jam. Node.js is the old sedan that stalls at the first sign of congestion. Go is a regular automatic. Rust is the hybrid that stays smooth at a crawl. They all get stuck, but some handle it with more grace.

How Many Outages Could Rust’s Async Model Prevent?

They did something practical: took those six historical outages and asked one question about each.

Could Rust’s async model have prevented this bug at the root? Not “made it faster.” Prevented.

Results:

- 2 outages involved accidental blocking inside async contexts. In Rust, blocking in an async context produces obvious compiler warnings and type conflicts.

- 1 involved silent queue growth. Rust’s channel types have built-in capacity limits, and backpressure patterns are explicit.

- 1 involved shared mutable state across await points. Rust’s ownership system demands explicit synchronization.

- 2 involved retry-induced fan-out storms. Rust can’t prevent these either — that’s an architectural problem.

Four out of six could have been prevented. Not “detected faster” — “harder to write incorrectly.”

It’s like the difference between a stove designed so you can’t forget to turn it off, versus a kitchen with a smoke detector. One prevents the fire. The other responds to it.

Code Reviews Started Sounding Different

They began explicitly marking async boundaries in architecture diagrams:

[HTTP Request]

│

▼

[Handler Future]

│

├── spawn_blocking ──► [Legacy Sync Call]

│

└── async channel ──► [Worker Task Pool]

Before Rust, these boundaries were conceptual — everyone had a mental model, but nothing in the code enforced it. After Rust, these boundaries became contracts, enforced by the type system.

Code review conversations shifted from “looks fine” to:

- “Where does this Future yield?”

- “What happens when this channel fills up?”

- “Is this Mutex held across an await?”

These are uncomfortable questions. They’re cheaper than incident reports.

The Trade-offs Are Real

None of this was free.

Compile times are genuinely long. Error messages sometimes read like riddles. Onboarding takes longer. Some libraries aren’t mature yet. You write more code than the equivalent Go or Node.js.

The first two months, development velocity dipped. The following nine months, operational incidents dropped.

How that math works out depends on your team. If your service is an internal tool with a few dozen daily users, Rust is probably overkill. If your service is a user-facing critical path where outages wake people up at 2 AM, it’s worth doing the math carefully.

The Quietest Change

The biggest shift wasn’t the RPS numbers.

It was the tone of the postmortems.

The old ones always contained phrases like:

- “Unexpected scheduler interaction”

- “Subtle event loop stall”

- “Hidden backpressure issue”

The new failures were boring: bad config, botched deploy, downstream timeout.

Boring failures are good failures. Boring means predictable, and predictable means preventable. The “mysterious scheduler issues” are the scary ones — you don’t know when they’ll show up, and when they do, you can’t find them.

Final Thoughts

Async systems are coordination machines at heart. When they fail, they don’t explode — they spread latency across every request like peanut butter on toast. The languages used before weren’t wrong. They were just more forgiving.

Rust’s async model is strict. That strictness surfaces failure modes earlier. Not perfectly, not magically. Just earlier.

Async Rust didn’t make anyone smarter. It just made certain mistakes louder. When you’re operating real systems, loud mistakes cost less than quiet ones.

If you’ve ever watched a latency graph climb while CPU sat perfectly still, you know the feeling. They kept the Rust service because it bent later. Sometimes, that’s enough.

Async System Health Checklist:

- Any synchronous blocking calls inside async functions? (File IO, CPU-heavy computation, sync locks)

- Any locks held across await points?

- Do channels/queues have capacity limits? What’s the backpressure strategy?

- Does retry logic have exponential backoff and max retry limits?

- Is p99 latency monitored with its own alert? (Don’t just watch averages)

- Are async/sync boundaries marked in architecture diagrams?

Has your team ever experienced the “everything looks fine but it’s slow” ghost? Share your war stories in the comments.

FAQ

How much faster is async Rust compared to Go and Node.js?

Raw RPS comparisons don’t tell the full story. In the load test above, Rust+Tokio sustained 31k RPS, Go hit 24k, and Node.js managed 21k. But the real gap is in the degradation curve: at 2x load, Rust’s p99 was 140ms versus Go’s 870ms and Node.js’s 1.2s. Rust’s advantage isn’t “faster” — it’s “degrades later under pressure.”

Can the Rust compiler catch all async bugs?

No. Out of 6 historical outages, Rust’s type system and ownership model could have prevented 4 at the source (blocking mixed into async contexts, unbounded queue growth, shared mutable state across await points). But fan-out amplification from retry storms is an architectural problem that no language can prevent — you need exponential backoff and circuit breakers at the system level.

Is it worth migrating from Node.js or Go to async Rust?

Depends on your context. For internal tools with a handful of daily users, the migration cost far outweighs the benefit. For user-facing critical paths where outages trigger 2 AM pages, it’s worth running the numbers: expect slower development for the first couple of months, but fewer operational incidents afterward. You don’t need to migrate everything — start with one new service and see how it goes.