The C10M Problem in 2026: Why Your 128-Core Server Still Can't Handle 10 Million Packets Per Second

C10M: The 4 AM Lesson

Forty thousand dollars.

That’s the Slack message I got from finance at 4 AM. Not asking me, but telling me: last month’s AWS bill looked like a phone number.

I opened up the monitoring dashboard—64 cores all maxed out, packet loss climbing past 25%, and I’m still sitting there thinking maybe we need a bigger instance.

We were running a real-time bidding platform. 50-byte packets, millions per second, sub-millisecond SLA requirements. This kind of traffic looks great on PowerPoint, but when you actually run it, it’s another story.

Here’s something nobody tells you upfront: once you hit 2 million packets per second, the Linux network stack just lies down. Not some graceful degradation either—it thrashes like a drowning person.

This is the C10M problem. C10K is 10,000 connections per second. C10M just adds a zero—10 million. Someone brought this up back in 2012, but the Linux kernel still can’t handle it.

The C10M problem: When packet rates surpass 2 million per second, the Linux network stack simply gives up

The C10M problem: When packet rates surpass 2 million per second, the Linux network stack simply gives up

The Doorman Syndrome

The Linux kernel network stack has been around for decades. Works great most of the time. But when you really push the traffic, it starts falling apart.

Back in the 90s or early 2000s, 100,000 packets per second was considered top-tier. Every packet was treated like a VIP guest: its own interrupt, its own memory copy, even a tour through netfilter’s checkpoints.

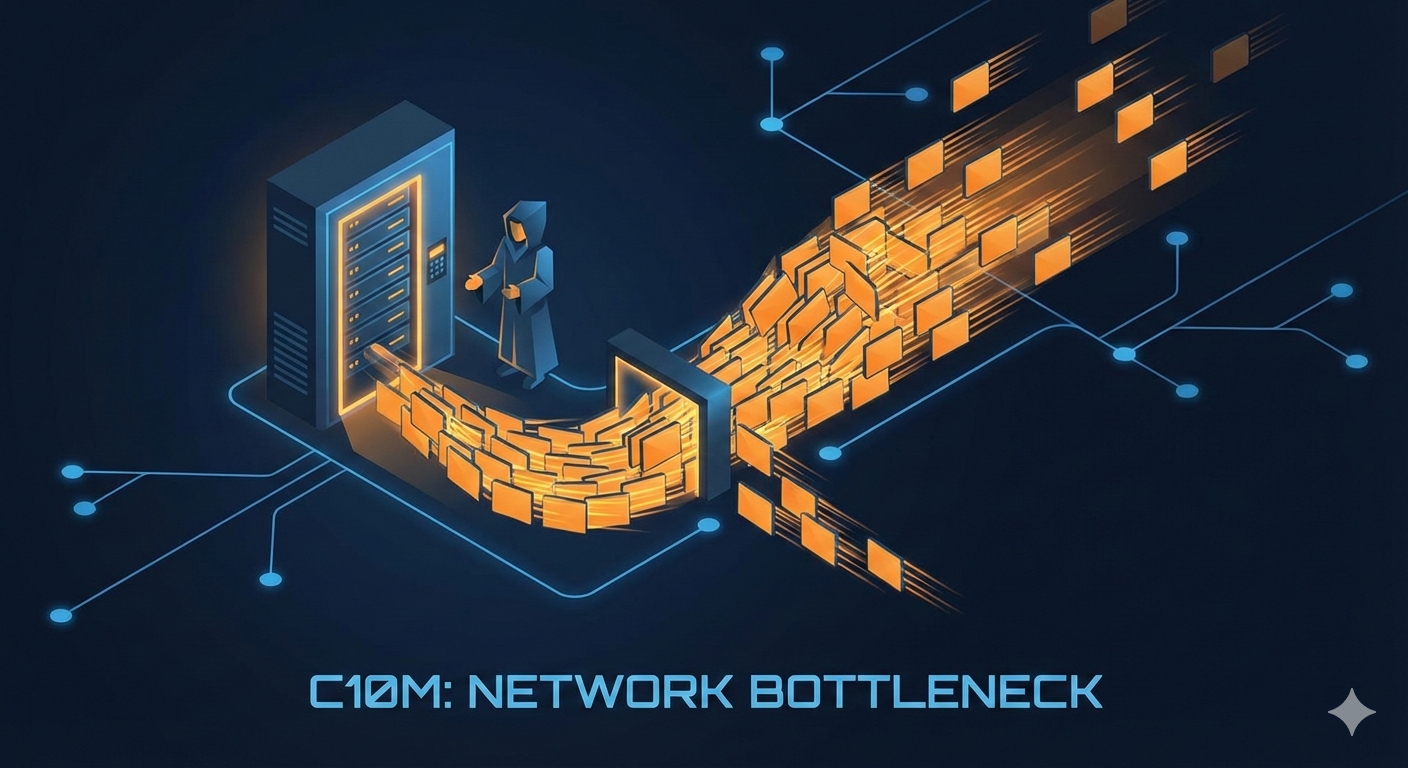

Packet arrives at the NIC. Doorbell rings (interrupt). CPU drops everything, switches into kernel mode, copies the buffer, marches it through the iptables maze, pushes it up the TCP/IP stack, copies it again into userspace. Every single packet runs this gauntlet.

At 1 million packets per second, the CPU is so busy answering the door it never gets around to reading the mail. Each context switch costs about 1,500 to 3,000 CPU cycles. At 2 million packets, your entire CPU budget is gone before you’ve even looked at the payload. This is why C10M needs a completely different approach.

We had about 50 iptables rules configured. Connection tracking, sanity checks—stuff you don’t notice at low speeds, but at scale it becomes dead weight. Every packet has to run these gauntlets. That’s 100 million checks per second.

You’re not processing data anymore. You’re running the world’s most expensive telephone switch.

The first time I saw a traffic spike, I stared at htop like it was a car engine redlining in neutral. All cores maxed out, application threads getting maybe 5% CPU time. The rest was all the kernel arguing with itself about who gets to touch the packet next.

DPDK: Kicking the OS Out the Door

DPDK—this whole kernel bypass thing—sounded ridiculous when I first heard it. You’re basically telling the operating system “thanks but no thanks” and mapping the NIC’s DMA memory directly into your application.

Left: Traditional Linux network stack with multiple processing layers, Right: DPDK’s zero-copy direct path

Left: Traditional Linux network stack with multiple processing layers, Right: DPDK’s zero-copy direct path

Like having packages delivered directly to your door instead of making every parcel go through the post office, get sorted three times, stamped, logged, and then delivered. Packets land in memory and your code just reads them. No middleman.

DPDK isn’t a library—it’s an eviction notice for your OS. Intel’s way of telling you the kernel layer was always optional.

But the price hits you immediately: you lose everything. No TCP stack. No socket API. No netstat, no tcpdump, no familiar safety nets. Your NIC just… disappears from the OS entirely.

Setting this up feels less like programming and more like defusing a bomb in a dark room. You have to carve out Hugepages like you’re claiming territory in a war zone—reserving memory at boot before the kernel can touch it:

// Burn the boats - kernel can't have this NIC back until reboot

// One-time nuclear option: ./dpdk-devbind.py --bind=vfio-pci eth1

struct rte_eth_conf port_conf = {

.rxmode = {

.mq_mode = RTE_ETH_MQ_RX_RSS, // RSS or die: spread the fire across cores

},

};

// This is where you steal the hardware from the OS

rte_eth_dev_configure(port_id, nb_rx_queues, nb_tx_queues, &port_conf);

// Pre-cook a pool of packet buffers (kernel used to babysit this)

struct rte_mempool *mbuf_pool = rte_pktmbuf_pool_create(

"MBUF_POOL",

8192, // Go too low and you'll starve under load

250, // Per-core cache for lockless perf

0, // Private data size - usually just zero

RTE_MBUF_DEFAULT_BUF_SIZE, // 2KB chunks

rte_socket_id() // Pin to local NUMA or suffer the latency tax

);

Run that, and your NIC vanishes. ip link show won’t see it. It’s gone. It belongs to your process now, and the kernel is just standing there wondering what happened to its hardware.

Once you’ve cleared the OS out of the way, the actual loop is almost too basic to believe:

while (1) {

struct rte_mbuf *bufs[32]; // Batching is everything - cache locality

// Poll hardware directly - no waiting, no syscalls

uint16_t nb_rx = rte_eth_rx_burst(port_id, queue_id, bufs, 32);

// Whatever showed up this cycle is yours now

for (int i = 0; i < nb_rx; i++) {

// Your packet logic - parse, route, respond

// All userspace memory, zero-copy from NIC

process_packet(bufs[i]);

}

// Return the buffers or you'll leak and die

rte_pktmbuf_free_bulk(bufs, nb_rx);

}

The result was almost insulting: 8 cores sat there yawning at 40% load, doing the same work that previously had 64 cores redlining and failing. Same traffic pattern. Same packet count. I thought we’d introduced a bug that was silently dropping packets. Nope. Just… actually efficient for once.

XDP: The Surgical Strike

If DPDK is the nuclear option, XDP is the surgical strike. You’re still in the kernel’s house, but you’re working in the mudroom, checking IDs through the peephole before packets can even knock on the door. Your eBPF code runs at the driver layer, intercepting packets before they touch the network stack.

// Runs in kernel space but at the driver level - pre-everything

SEC("xdp")

int xdp_drop_garbage(struct xdp_md *ctx) {

void *data = (void *)(long)ctx->data; // Packet start

void *data_end = (void *)(long)ctx->data_end; // Boundary

struct ethhdr *eth = data;

// eBPF verifier is paranoid - bounds check or program rejected

if ((void *)(eth + 1) > data_end)

return XDP_DROP; // Malformed, kill it at the door

// Anything not IPv4 dies here, kernel never sees it

if (eth->h_proto != htons(ETH_P_IP))

return XDP_DROP;

return XDP_PASS; // Let real traffic through to normal processing

}

We use this for DDoS mitigation now. When we got hit with 5 million PPS last month—some script kiddie with a botnet and too much time—XDP executed 4.8 million garbage packets in the driveway before they could even knock. The kernel never saw them. CPU usage barely moved. The remaining 200k legitimate packets got normal processing like nothing was happening.

But the honeymoon with XDP ends the second you need to track state. The eBPF verifier starts screaming at you. No unbounded loops. No “maybe this pointer is valid” nonsense. If it thinks you might crash the kernel, your program gets rejected. For simple packet filtering? Perfect. For stateful processing or complex protocols? You’re back to DPDK whether you like it or not.

The Cost: Price of Admission

Here’s the price of admission: you’re effectively deleting your entire ops playbook. All your monitoring? Gone. Security tools? Useless. That debugging muscle memory you spent years building? Wrong environment entirely.

Need to capture traffic? tcpdump sees nothing, so you’re writing custom tooling from scratch. Want connection stats? Better build that into your app. Firewall rules? That’s your problem now—every bit of security logic lives in your code, and when it breaks, there’s no kernel to blame.

The debugging sessions were pure psychological warfare. We had a memory leak that took three weeks to find. Three weeks of staring at hex dumps until my eyes bled. Standard tools couldn’t see DPDK’s memory pools. gdb attached but showed garbage. valgrind was completely blind. We ended up instrumenting the code with custom stats dumps every 10 seconds, then manually correlating with NIC counters like we were debugging assembly in 1985.

And deployment? We had a production push fail because someone—let’s call him Dave because I’m still mad about it—forgot to rebind the NIC to vfio-pci after a kernel update. Dave thought the automation script handled the rebind. It didn’t. The application started fine, found zero DPDK-controlled NICs, and just sat there in silence. No errors. Process running. Health checks passing. The monitoring dashboard looked like a flatline on a heart monitor. We weren’t failing; we were just… absent. Dave spent 45 minutes looking at application logs while the NIC was sitting in the corner, ignored by the entire world.

Benchmark: When Theory Survives Contact with Reality

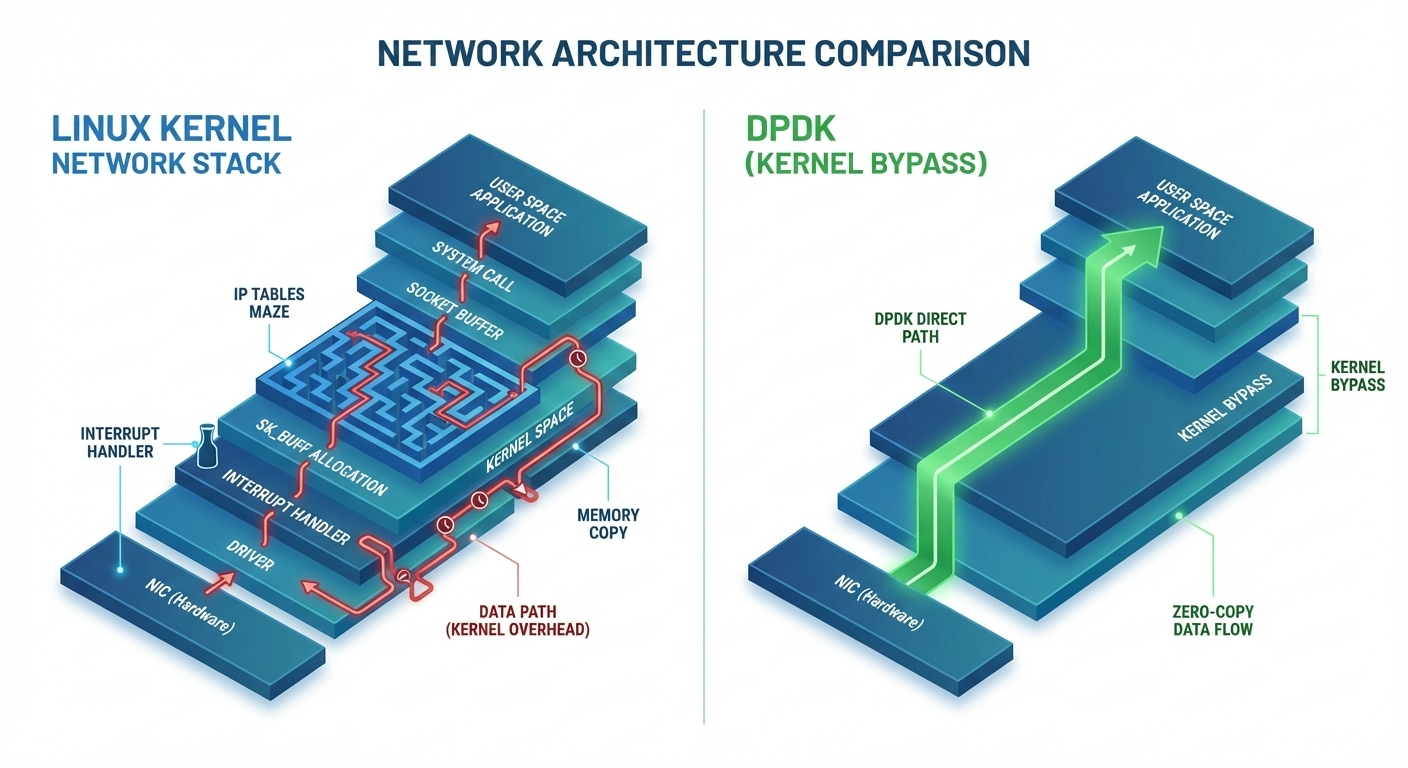

We put two identical boxes side-by-side—both packing dual Xeon 6138s, both with Intel X710 NICs—and threw the same UDP flood at them to see which one would break first.

We threw every “Best Practices” blog post at the kernel—pinning IRQs until we were blue in the face, cranking ring buffers to the moon, configuring RPS and RFS like our lives depended on it. Didn’t matter. 32 cores were fighting for their lives just to hit 1.8M PPS while dropping 18% of the traffic. The fans sounded like a jet engine on the tarmac. The louder the fans got, the more packets we dropped. It was a literal siren for our failing architecture.

Benchmark results: Kernel networking struggles at 1.8M PPS, DPDK comfortably reaches 9.2M PPS

Benchmark results: Kernel networking struggles at 1.8M PPS, DPDK comfortably reaches 9.2M PPS

DPDK implementation, same workload: 9.2M PPS sustained. 12 cores at 60%. Packet loss under 0.001%, and most of that was bugs in our userspace logic, not the framework.

Kernel networking is great when you’re just cruising at low speeds. But once you cross that 1M PPS threshold, things start to wobble. By 2M, the wheels come off entirely, and you’re just paying Amazon for the privilege of watching your CPU thrash itself to death on context switches.

Warning: Containment Failure

You know what’s worse than kernel networking choking at 2M PPS? Your DPDK app with a buffer leak at 10M PPS. At that packet rate, you can exhaust NIC buffers in under three seconds. We had an off-by-one error in buffer recycling that caused a complete meltdown during peak traffic. That month’s SLA graph showed a jagged drop that looked like someone had taken a hacksaw to it. Recovery meant full restart, which meant dropping everything for five seconds while the CFO’s Slack DMs got increasingly creative with profanity.

Good luck finding anyone who can actually maintain this. I asked a distributed systems guru—guy had papers at NSDI, could talk about Paxos for hours—how to handle a cache miss in a lockless ring buffer, and he looked at me like I was speaking Martian. He didn’t know what a TLB miss was. We interviewed network engineers who could recite RFCs in their sleep but couldn’t debug a memory leak without a GUI. The Venn diagram overlap is microscopic.

And it compounds. Every kernel upgrade means re-testing hugepage configs. Every NIC firmware update is a potential landmine. We maintain a separate staging environment just for packet processing because the failure modes are too weird for normal QA to catch.

But honestly? If you’re actually pushing past 5M PPS in production, you don’t have options. The kernel will fail. Not because it’s badly designed—it’s excellent for 99.9% of use cases—but because the assumption that the CPU is faster than the network is dead. That assumption collapsed somewhere around 2015, and we’ve been living in the fallout ever since.

Don’t do this because it’s cool. Do it because you’re out of other options and you’ve already tried everything else. Kernel bypass works, it’s terrible, and I’ve lost more sleep over it than any other architectural decision in my career.

Final Thoughts

The Linux kernel network is like an over-enthusiastic doorman. Great at low speeds, but at millions of packets per second, it’s too busy answering the door to process the mail.

A few reference points:

- Under 1M PPS? Kernel networking is fine, don’t bother

- 1-2M PPS? Optimize interrupts, buffers, RSS, you can squeeze more

- Over 2M PPS? Consider DPDK or XDP, but prepare to throw away your entire ops toolbox

- DPDK is the nuclear option, XDP is the surgical strike

- Most importantly: this stuff is brutal to maintain, finding people who understand it is harder than finding a compatible partner

What step of network traffic processing is giving you the most headaches right now? Haven’t hit the bottleneck yet, or already struggling at the million-packets-per-second edge? Or have you already fallen into the DPDK trap?

Next time we can talk about how to observe these high-performance systems—after all, you’ve bypassed the kernel, traditional monitoring tools are basically blind. Or want to know how to implement a TCP stack in userspace? That’s another deep rabbit hole, but others have been there, and we can avoid those pitfalls.

Found this article helpful?

- Like it to help more people see it

- Share it with friends or colleagues who might need it

- Follow Dream Beast Programming for more practical tech articles

- Have questions or thoughts? Join the discussion in the comments

Your support is the greatest motivation for me to keep creating!