The Truth About Rust Cold Starts on AWS Lambda: Those Scary Numbers

Table of Contents

- Casual Opening

- What the Heck is a Cold Start Anyway?

- That Headache-Inducing 412 Milliseconds

- A Fair Comparison Experiment

- When Traffic is Stable, Everyone’s Happy

- The Complete Cold Start Journey

- Why Rust “Loses”: An Unfair Starting Line

- Actually Useful Optimization Strategies: Be Lazy

- My Current Selection Criteria: Dress for the Occasion

- Final Words: No Best, Only Most Suitable

Casual Opening

The other day I was having tea with a backend developer friend, and he looked at me with a worried face: “Buddy, I recently jumped on the trendy bandwagon and moved my service to AWS Lambda.”

I thought, wow, this guy’s pretty hip - serverless, pay-per-use, auto-scaling, sounds like opening a buffet restaurant where you only start cooking when customers arrive. So convenient.

But his next sentence made me stop smiling: “Those cold starts are killing me.”

He said one night the system had been quiet for a while, like a library at midnight. Then suddenly a user request came in, and guess what? It took 412 milliseconds to return.

What’s 412 milliseconds? About the time it takes to blink three times. Doesn’t sound long, right? But in a user’s eyes, it’s like walking into a convenience store where the cashier slowly counts money behind the counter, only looking up to ask what you want after finishing. Even if they scan quickly afterwards, you’re already thinking: “Is this store going out of business?”

What the Heck is a Cold Start Anyway?

Let’s get the concepts straight first, don’t be scared by those fancy terms.

A cold start isn’t one single thing; it’s more like a series of small troubles all piled onto the first unlucky request, like your first time at the gym:

Lambda needs to find you a treadmill (create runtime environment) You need to put on your sneakers (runtime startup) You need to set up your water bottle and towel (load binary and shared libraries) You need to warm up (various library initializations) Then you can start running (your code starts working)

The second time you go to the gym, you can start running right away - that’s a warm start. And that first-time user is the one paying the “cold start” price.

That Headache-Inducing 412 Milliseconds

My friend’s service is actually pretty simple, like going to a convenience store to buy water: verify a JWT token (scan to pay), query one row from the database (grab water from the shelf), return JSON (hand you the water).

Normally, a warm start takes under 20 milliseconds, like an experienced convenience store employee who knows what you want before you even speak.

But here’s the problem: users don’t come at your pace. Like at noon when everyone suddenly gets hungry and rushes into restaurants. At that moment, every request could be a “first time.” That 412-millisecond delay won’t crash the system, but it’s enough to make users think “this app is a bit laggy.”

Once users get that impression, it’s like discovering the convenience store cashier is always a beat slow - next time you might go to the supermarket next door.

A Fair Comparison Experiment

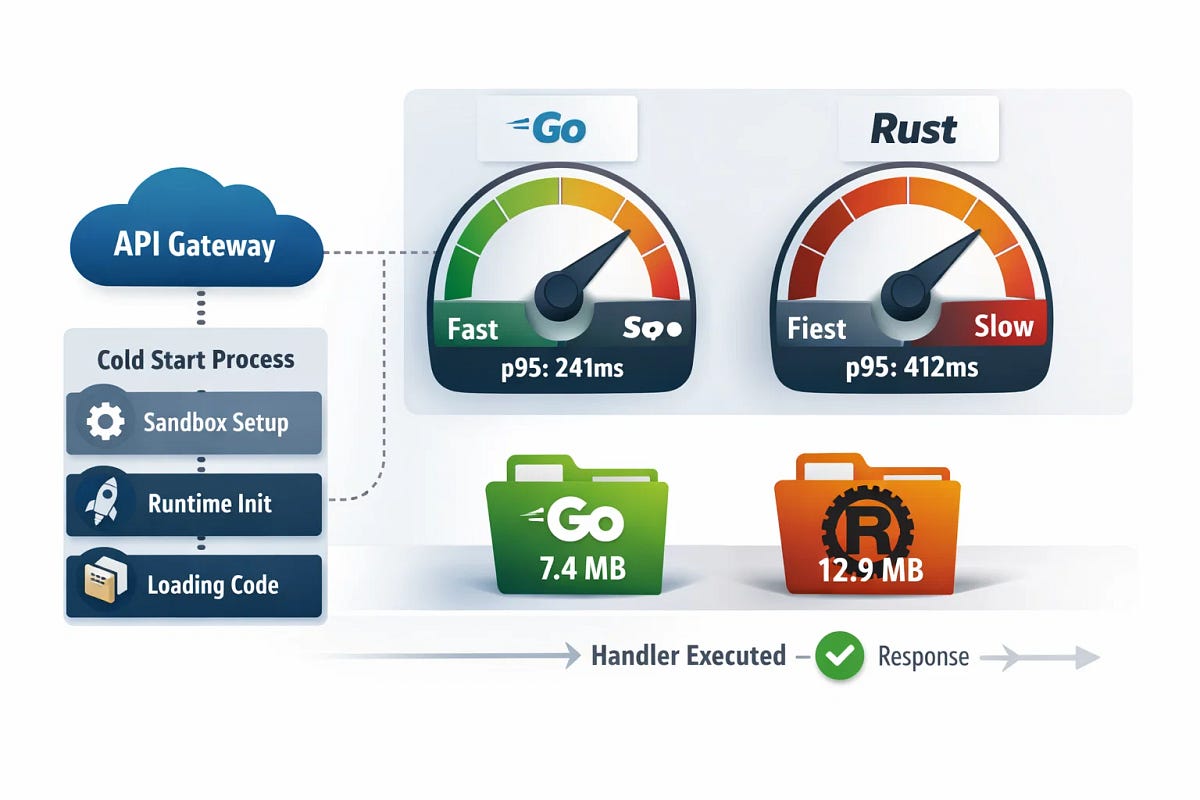

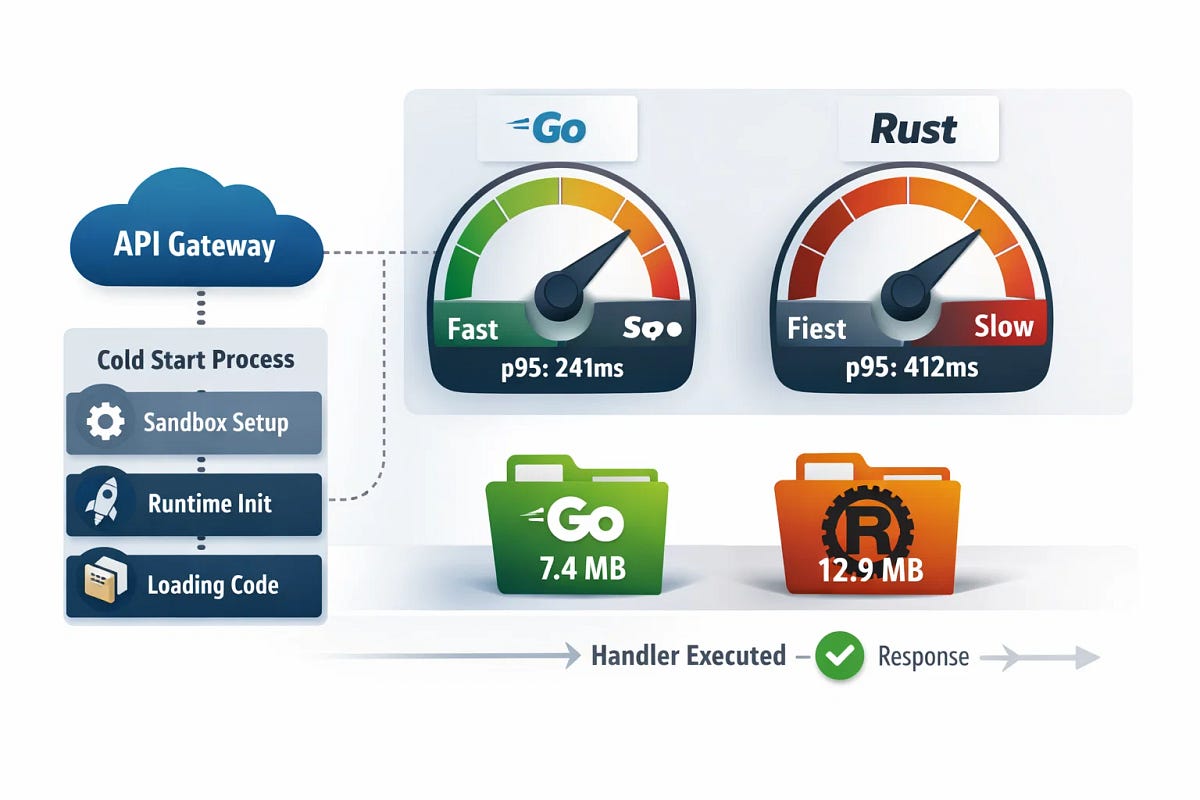

After chatting with him, I ran a little experiment myself, like timing two athletes in a 100-meter dash.

Go and Rust standing on the same starting line: Same processor logic (same track) Same memory settings (same sneakers) Same region (same weather) Same deployment method: single binary, API Gateway forwarding to Lambda (same referee)

I measured p50 and p95 initialization times, then intentionally let the function idle for a while before sending the first request, like making athletes take a nap before competing.

This isn’t some scientific benchmark, but it’s enough to make the point.

With x86_64 architecture, 512MB memory, ZIP deployment, API Gateway REST configuration, here are the results:

| Language | Cold Start p50(ms) | Cold Start p95(ms) | Binary Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Go | 118 | 241 | 7.4 MB |

| Rust | 176 | 412 | 12.9 MB |

See that p95 number? 412 milliseconds vs 241 milliseconds. That’s the gap that makes users frown, like two delivery people - one waits 3 seconds after knocking, the other waits 7 seconds.

When Traffic is Stable, Everyone’s Happy

Actually, when traffic is stable and functions stay warm, both languages perform well. Go and Rust can both keep warm start latency under tens of milliseconds, like two skilled baristas who can make you a latte in under 30 seconds.

The problem is, real-world traffic is never a straight line.

It’s like morning rush hour subway - sometimes the car is empty, sometimes a huge wave of people suddenly pours in. When traffic is bursty, that p95 number matters more than any average.

Why? Because users don’t remember how “average” fast you are; users remember that pause that made them wait. Like you won’t remember how fast the delivery person is on average, you’ll only remember that time they waited 10 minutes downstairs before coming up.

The Complete Cold Start Journey

Let me draw you a picture of what actually happens on the cold start journey, like tracking a food delivery order:

Client Request (you place order)

↓

API Gateway (restaurant accepts order)

↓

Lambda Service (kitchen starts preparing)

↓

+--→ Create sandbox environment, mount code (find pan, turn on stove)

↓

+--→ Runtime startup (chef puts on apron)

↓

+--→ Load binary and shared libraries (get ingredients, spices)

↓

+--→ Initialization phase (your code runs here) (chop vegetables, marinate meat)

↓

Handler function called (start cooking)

↓

Return response (delivery sent out)

Every plus sign is a potential bottleneck. If your initialization phase does too much, like a chef insisting on grinding pepper fresh or making stock from scratch, those delays become user anxiety.

Why Rust “Loses”: An Unfair Starting Line

Let me be clear about this: Rust cold starts aren’t slow because Rust itself is slow. Like a sports car stuck in city traffic - it’s not that the car is slow, it’s that the road conditions are bad.

Rust cold starts are slow usually because the built artifacts need to do more work during initialization, like:

Binary file is too big: Rust-compiled programs are like luxury RVs - they have everything: leather seats, built-in fridge, panoramic sunroof. Loading such a big chunk takes time, like backing an RV out of the garage - you have to go slow.

Default async runtime initialization is heavy: Rust’s async runtime is like a complex sound system that needs to check all speakers, adjust equalizers, and connect Bluetooth on startup. Go’s runtime is more like a radio - press the button and you can listen.

TLS stack and crypto providers load on first use: This is like using a new safe for the first time - you need to set the password, try opening it a few times. The second time, it opens right away.

Logging and tracing subscribers do too much at startup: Like some people who need to organize their desk, make tea, and adjust lighting before starting work. While others can sit down and get to work.

Go in Lambda scenarios typically has smaller binary files, like a small electric car - quick to start, nimble to turn. The runtime’s first-start behavior is also smoother, like an experienced driver - everything flows naturally.

But this doesn’t mean Rust is bad. In warm start performance and tail latency under load, Rust can definitely surpass Go. Like once on the highway, the sports car can leave the electric car far behind.

It’s just that in the Lambda cold start game, the rewards go to those boring, small, lazy-initialized things. Like a fast-food competition - whoever serves first wins, regardless of how good your burger tastes.

Actually Useful Optimization Strategies: Be Lazy

Cold start optimization isn’t some mysterious technique; the core idea is just one: don’t do anything until you have to. Like a smart chef who never chops vegetables before the order comes in.

A few strategies that actually showed results in my charts:

Don’t work during initialization: Clients should be lazily initialized. Config can be parsed early, but don’t rush to establish network connections. Like you can put the recipe on the table, but don’t turn on the stove yet.

Shrink the binary: Strip symbols, choose smaller dependency trees. Like traveling - only bring essentials, don’t pack your whole house.

Use ARM64 if you can: For many workloads, ARM64 not only costs less but also has better cold start performance, mainly because you get more memory for the same money. Like with the same budget, renting a small apartment is more practical than renting just the living room of a big villa.

Choose the right deployment method: For some teams, container images increase cold starts; for others, they stabilize things. Test it yourself, don’t guess. Like buying shoes - you need to try them on, can’t just look at the size.

Here’s a simple Go handler example that keeps initialization boring, like a zen waiter:

package main

import (

"context"

"github.com/aws/aws-lambda-go/lambda"

)

func main() {

lambda.Start(handler)

}

A Rust handler with the same spirit, doing nothing at startup:

use lambda_runtime::{run, service_fn, Error, LambdaEvent};

use serde_json::Value;

async fn handler(_: LambdaEvent<Value>) -> Result<Value, Error> {

Ok(serde_json::json!({"ok": true}))

}

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<(), Error> {

run(service_fn(handler)).await

}

When compiling Rust, I use those boring but practical options: release profile, strip symbols, don’t enable unused features. Like packing luggage - only bring essentials, throw away all decorations.

Smaller binary, less pain. Like traveling light - easier to run.

My Current Selection Criteria: Dress for the Occasion

I don’t argue on Slack anymore about which language is better, like I don’t argue about whether suits or athletic wear are better.

I’ve started treating cold starts as a product requirement. Like choosing clothes - it depends on the occasion.

If an endpoint is user-facing and traffic is bursty, I’ll optimize for the first request, not the tenth. Like opening a fast-food restaurant - you need to make sure the first customer doesn’t wait too long.

Sometimes this means using Go, like wearing sneakers for hiking.

Sometimes this means using Rust, but strictly controlling dependencies, like wearing a suit but no tie.

But no matter what, one thing is certain: the first real user must be part of your benchmark. Like trying on clothes - you need to look in the mirror, can’t just read the label.

Final Words: No Best, Only Most Suitable

Technology selection is never a multiple-choice question. Go and Rust are both great, but they have different strengths in different scenarios, like hammers and screwdrivers - both are good tools, but for different purposes.

The Lambda cold start game taught me: don’t assume, measure. Your usage patterns, your traffic characteristics, your user expectations - these are the deciding factors. Like buying shoes - you need to try them on yourself, can’t just look at ads.

Next time someone says “Rust is faster” or “Go is simpler,” you can ask: “In what scenario?” Like someone praising how fast sports cars are, you can ask: “What about during city traffic jams?”

Did you find this article helpful? Like + Share, so more friends can see this content. Share it with friends working on cloud native or server-side development. Follow the WeChat public account “Dream Beast Programming” for more technical insights. See you next time!